Read Will Rogers column 88 years ago: September 1, 1935

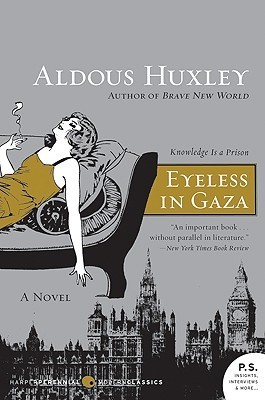

Written at the height of his powers immediately after Brave New World, Aldous Huxley’s highly acclaimed Eyeless in Gaza is his most personal novel. Huxley’s bold, nontraditional narrative tells the loosely autobiographical story of Anthony Beavis, a cynical libertine Oxford graduate who comes of age in the vacuum left by World War I.

1“The problem is that the narrative is non-linear. Each chapter is dated, and the dates jump back and forth between the 1890s to the mid-1930s. And this is where I think it was overly intellectual. Sure, it has a very modern and atypical narrative structure, but was there a point why that was the case? In order to understand the novel, I had to consult several literary resources to explain to me what the book was about. If I had not done that, and simply relied on the book, it would be a way worse experience for me. I ask myself why did Huxley choose to structure this novel in a non-linear way, but I fail to find an answer aside from assuming that he did so just because he could, period. No added effect intended”

2“Eyeless in Gaza is a result of a philosopher attempting to write a novel. It’s the same problem that plagues Ayan Rand, Friedrich Nietzsche (to a far less degree), and now Huxley. When fiction becomes a mode to simply propagate one’s thoughts, ideologies, or philosophy in such an explicit and rash manner, reading becomes a hassle. We read novels for narratives, for stories that introduce us to ideas implicitly in character’s decisions, in stylistic choices, in dialogue, and in story line. The best novels are those in which great writers — deliberately or unconsciously — explore philosophical questions by the narrative alone.”