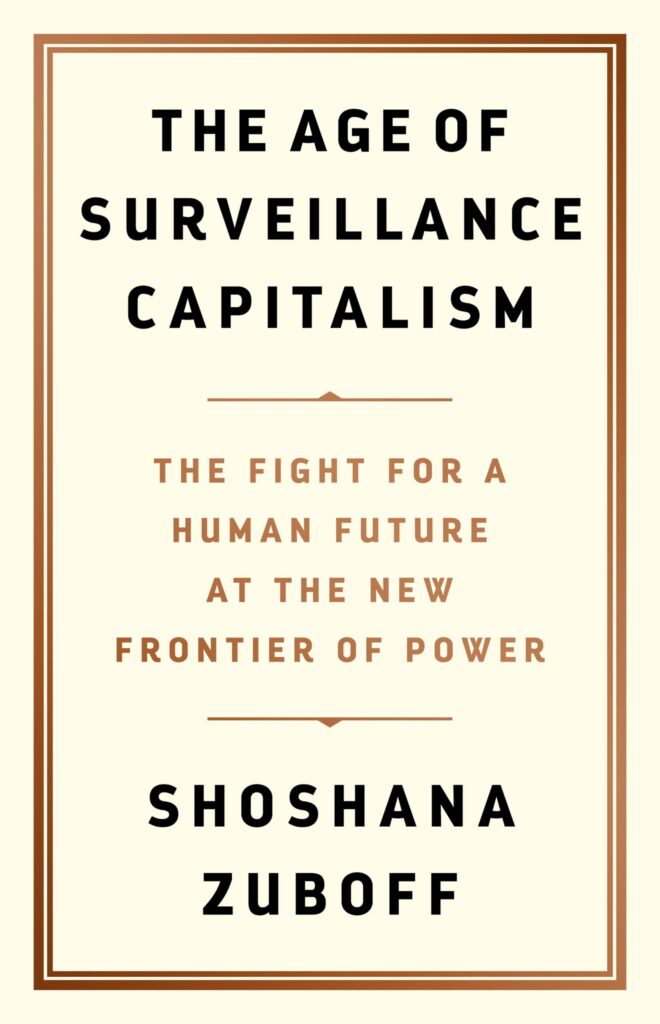

“The challenges to humanity posed by the digital future, the first detailed examination of the unprecedented form of power called “surveillance capitalism,” and the quest by powerful corporations to predict and control our behavior.

In this masterwork of original thinking and research, Shoshana Zuboff provides startling insights into the phenomenon that she has named surveillance capitalism.

Zuboff vividly brings to life the consequences as surveillance capitalism advances from Silicon Valley into every economic sector. Vast wealth and power are accumulated in ominous new “behavioral futures markets,” where predictions about our behavior are bought and sold, and the production of goods and services is subordinated to a new “means of behavioral modification.”

The threat has shifted from a totalitarian Big Brother state to a ubiquitous digital architecture: a “Big Other” operating in the interests of surveillance capital. Here is the crucible of an unprecedented form of power marked by extreme concentrations of knowledge and free from democratic oversight. Zuboff’s comprehensive and moving analysis lays bare the threats to twenty-first century society: a controlled “hive” of total connection that seduces with promises of total certainty for maximum profit — at the expense of democracy, freedom, and our human future.

With little resistance from law or society, surveillance capitalism is on the verge of dominating the social order and shaping the digital future — if we let it.” — Book promo @ goodreads.com

This is the existential contradiction of the second modernity that defines our conditions of existence: we want to exercise control over our own lives, but everywhere that control is thwarted. Individualization has sent each one of us on the prowl for the resources we need to ensure effective life, but at each turn we are forced to do battle with an economics and politics from whose vantage point we are but ciphers. We live in the knowledge that our lives have unique value, but we are treated as invisible. As the rewards of late-stage financial capitalism slip beyond our grasp, we are left to contemplate the future in a bewilderment that erupts into violence with increasing frequency. Our expectations of psychological self-determination are the grounds upon which our dreams unfold, so the losses we experience in the slow burn of rising inequality, exclusion, pervasive competition, and degrading stratification are not only economic. They slice us to the quick in dismay and bitterness because we know ourselves to be worthy of individual dignity and the right to a life on our own terms.

That the luxuries of one generation or class become the necessities of the next has been fundamental to the evolution of capitalism during the last five hundred years. Historians describe the “consumer boom” that ignited the first industrial revolution in late-eighteenth-century Britain, when, thanks to visionaries like Josiah Wedgewood and the innovations of the early modern factory, families new to the middle class began to buy the china, furniture, and textiles that only the rich had previously enjoyed.

Varian casts personalization as a twenty-first-century equivalent of these historical dynamics, the new “necessaries” for the harried masses bent under the weight of stagnant wages, dual-career obligations, indifferent corporations, and austerity’s hollowed-out public institutions. Varian’s bet is that the digital assistant will be so vital a resource in the struggle for effective life that ordinary people will accede to its substantial forfeitures. “There is no putting the genie back in the bottle,” Varian the inevitabilist insists. “Everyone will expect to be tracked and monitored, since the advantages, in terms of convenience, safety, and services, will be so great… continuous monitoring will be the norm.”

It is useful to note that despite the much-touted social advantages of always-on connection, social trust in the US declined precipitously during the same period that surveillance capitalism flourished. According to the US General Social Survey’s continuous measurement of “interpersonal trust attitudes,” the percentage of Americans who “think that most people can be trusted” remained relatively steady between 1972 and 1985. Despite some fluctuations, 46 percent of Americans registered high levels of interpersonal trust in 1972 and nearly 50 percent in 1985. As the neoliberal disciplines began to bite, that percentage steadily declined to 34 percent in 1995, just as the public internet went live. The late 1990s through 2014 saw another period of steady and decisive decline to only 30 percent.

Societies that display low levels of interpersonal trust also tend to display low levels of trust toward legitimate authority; indeed, levels of trust toward the government have also declined substantially in the US, especially during the decade and a half of growing connectivity and the spread of surveillance capitalism. More than 75 percent of Americans said that they trusted the government most or all of the time in 1958, about 45 percent in 1985, close to 20 percent in 2015, and down to 18 percent in 2017. Social trust is highly correlated with peaceful collective decision making and civic engagement. In its absence, the authority of shared values and mutual obligations slips away. The void that remains is a loud signal of societal vulnerability. Confusion, uncertainty, and distrust enable power to fill the social void. Indeed, they welcome it.

In the age of surveillance capitalism it is instrumentarian power that fills the void, substituting machines for social relations, which amounts to the substitution of certainty for society. In this imagined collective life, freedom is forfeit to others’ knowledge, an achievement that is only possible with the resources of the shadow text.

An abnormal division of learning marks both China and the West. In China the state vies with its surveillance capitalists for control. In the US and Europe the state works with and through the surveillance capitalists to accomplish its aims. It is the private companies who have scaled the rock face to command the heights. They sit at the pinnacle of the division of learning, having amassed unprecedented and exclusive wealth, information, and expertise on the strength of their dispossession of our behavior. They are making their dreams come true. Not even Skinner could have aspired to this condition.

For more than three centuries, industrial civilization aimed to exert control over nature for the sake of human betterment. Machines were our means of extending and overcoming the limits of the animal body so that we could accomplish this aim of domination. Only later did we begin to fathom the consequences: the Earth overwhelmed in peril as the delicate physical systems that once defined sea and sky gyrated out of control.

Right now we are at the beginning of a new arc that I have called information civilization, and it repeats the same dangerous arrogance. The aim now is not to dominate nature but rather human nature. The focus has shifted from machines that overcome the limits of bodies to machines that modify the behavior of individuals, groups, and populations in the service of market objectives. This global installation of instrumentarian power overcomes and replaces the human inwardness that feeds the will to will and gives sustenance to our voices in the first person, incapacitating democracy at its roots.

The dramatic, if largely unpublicised, recovery in Arctic sea ice is continuing into the New Year. Despite the contestable claims of the ‘hottest year ever’ (and even hotter in 2024), Arctic sea ice on January 8th stood at its highest level in 21 years. Last December, the U.S.- based National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) revealed that sea ice recorded its third highest monthly gain in the modern 45-year record. According to the science blog No Tricks Zone, the reading up to January 8th has now far exceeded the average for the years 2011-2020. It also exceeds the average for the years 2001-2010, and points directly upwards with regard to the average for the years 1991-2000. — Arctic Sea Ice Soars to Highest Level for 21 Years BY Chris Morrison

Friday morning when I drove to Sierra Vista I had some side winds starting in the Tombstone Canyon home of Old Bisbee. They continued to buffet me all the rest of the way there and back but not as bad on the return. It was later in the afternoon that the winds picked up at the Campground with winds in the 20-30 mph range and gust as high as 50 mph. It was still blowing hard around midnight when I took Erik out but had calmed a lot by the time we did our morning walk.

That book sounds good however I can’t imagine it’s enhancing my moods. .I am not really a cynical person however I consider my opinions to be based in reality,and

the book doesn’t sound fictionalized.

Driving in those conditions is challenging,I’m glad you and Erik are okay , Mary